Our research surprisingly revealed that the exhibition "State Art in Baden 1918–1933" held in Karlsruhe in April 1933, and the concurrently organized exhibition "Bolshevist Cultural Paintings" in Mannheim, were not the beginning of a new cultural-political development, but rather its dismal climax. Just two months after the National Socialists rose to power on January 30, 1933, these two exhibitions were the first ever in which modern artists were defamed. They served as the blueprint for the "Degenerate Art" exhibition, which launched in Munich in 1937 and was subsequently shown in many cities across Germany and Austria. In his editorial on April 10, 1933, Curt Amend, the editor-in-chief of the Karlsruher Zeitung, referred to the Karlsruhe exhibition as the "Chamber of Horrors" of art. This coined the term that, alongside the designation "Exhibition of Shame," subsequently became established throughout Germany.

The cultural struggle in Karlsruhe before 1933

One of the members of the committee that organized the Mannheim exhibition "Bolshevist Cultural Paintings" was Joseph August Beringer, a biographer of Thoma and editor of the Karlsruher Tagblatt. As early as 1925, in his scathing review of the Mannheim exhibition "New Objectivity," he had claimed:

„The acquisitions of the art galleries show that our public galleries are on their way to becoming [...] collections of evidence of mental and emotional illnesses. [...] It will then be time [...] to make the very honorable psychiatrists into ministers of art and directors of art galleries.“

This was stated in the Karlsruher Tagblatt on August 3, 1925. This cynical thesis shows that the defamation of modern art as the product of mentally ill people was by no means new. In Karlsruhe, the cultural struggle that reached its preliminary climax in the exhibition "Government Art 1918 – 1933" began as early as the beginning of the 1920s. In particular, the followers of Hans Thoma criticized, on the one hand, that the Baden Art Gallery (Badische Kunsthalle) was purchasing too many works by foreign painters and, on the other, that the acquired works were "inferior" because they were not realistic or even naturalistic.

Hans Thoma served as the director of the Badische Kunsthalle from 1899 to 1919. At the time of his retirement in 1919, he was 80 years old. His successor was the art historian Willy Storck, who was only 30 years old and led the Kunsthalle until his early death in August 1927. It was clear that a young art historian would pursue a different exhibition concept than a painter who primarily favored and purchased works representing his own artistic style. Thus, conflict within the Karlsruhe art scene was inevitable. During the years of hyperinflation starting in mid-1922, a third point of criticism emerged: despite many Baden painters facing existential hardship, the Kunsthalle continued to acquire works by non-Baden artists.

The Role of the Painter Hans Adolf Bühler

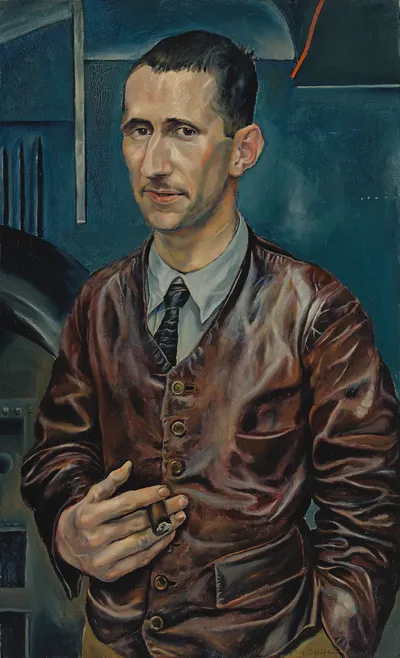

Bühler was a master student of Hans Thoma and deeply rooted in his symbolist and homeland-oriented tradition. Starting in 1914, he held a professorship at the Karlsruhe Art Academy, known then as the Landeskunstschule. While initially regarded as a representative of a pathos-filled Symbolism, he increasingly evolved into a leading voice against modernism. As early as the 1920s, Bühler positioned himself as a vehement opponent of the Weimar Republic and avant-garde art. In 1930, he took over the leadership of the Karlsruhe local branch of the Militant League for German Culture (Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur, KfdK) and was an active member of völkisch-nationalist associations that demanded a "cleansing" of German art from foreign and Jewish influences. Bühler is considered the primary instigator of the so-called "Karlsruhe Cultural Struggle," in which he systematically agitated against modern colleagues and the democratic cultural policies of the State of Baden. In 1931, he became a member of the NSDAP. His appointment as director of the Landeskunstschule in October 1932 served as a political signal for the growing strength of völkisch forces in Baden.

The Events in March 1933

On March 8, 1933, the NSDAP Gauleiter in Baden, Robert Wagner, was appointed Reich Commissioner in Karlsruhe by the Berlin government. The following day, he seized the Baden Ministry of the Interior on Schlossplatz with several hundred SA men. On March 11, the State President of Baden, Josef Schmitt, was removed from office. Wagner appointed the editor-in-chief of the NSDAP newspaper "Der Führer," Otto Wacker, as acting Minister of Education and Culture, and the director of the Landeskunstschule, Hans Adolf Bühler, as acting director of the Badische Kunsthalle.

Wacker and Bühler took immediate action: on March 11, Lilli Fischel, who had directed the Badische Kunsthalle since 1927, was "placed on leave" with immediate effect and retired on April 7. The legal basis for this was the "Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service," under which officials could be dismissed if they were of "non-Aryan descent" or if their political activities failed to guarantee that they would unreservedly support the National Socialist state at all times.

On March 16, Wacker and Bühler inspected the exhibition rooms of the Badische Kunsthalle and ordered the early closure of the exhibition featuring watercolors and drawings by the Pforzheim painter Emil Bizer, as well as the cancellation of two other exhibition projects initiated by Fischel. The Nazi newspaper "Der Führer" reported the following day:

“When Hans Thoma was handed his letter of resignation, an artistic movement began to move in that placed everything banal and non-essential in the foreground and stamped it as art. Distortion, gimmickry, exoticism—these were the three paths of the 'modern' line. Immense sums were thrown away here on paintings by Slevogt, Liebermann, Munch, Hofer, or Corinth, while at the same time, valuable art treasures from the Kunsthalle's collection were being sold off for a pittance on the international art market.

“The Minister of Education and Culture, Dr. Wacker, decreed that the people of Baden should see for themselves the artworks of the ‘cultural epoch of 1918-1933.’ In the very near future, a compilation will be made of those Bolshevist and morbid works that were purchased by the government during this period. The price is to be displayed under each painting, along with the name of the respective Minister of Education and Culture who was responsible. Then, a mass pilgrimage to the Kunsthalle must begin, and we know that the visitors will pass a unanimous judgment on that past era, in which everything was done to shatter our own distinct spiritual life.”

Facts about the exhibition from April 8 to 30, 1933

A total of 18 oil paintings and 79 watercolors and prints were displayed. The purchase prices were listed beneath the images, as were the names of the ministers responsible for art and education during whose terms the acquisitions were made. There was an "Erotic Cabinet" featuring drawings by students of the Landeskunstschule. Additionally, a list and photographs of artworks were exhibited—primarily second-rate Old Masters and 19th-century paintings—which had been sold from storage by Bühler's predecessors, Storck and Fischel, to increase the budget for purchasing modern art.

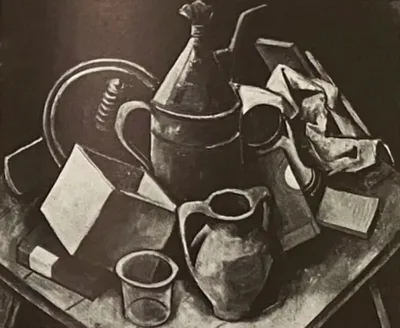

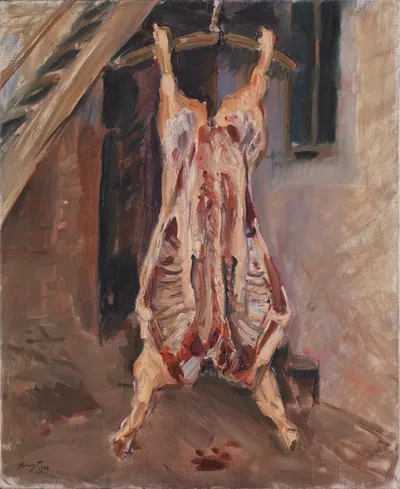

The oil paintings on display were by Bizer, Corinth, Erbslöh, Fuhr, Hofer, Kanoldt, Liebermann, von Marees, Munch, Purrmann, Schlichter, and Slevogt. Six of them can be seen on the right. Among the 79 drawings were works by Hubbuch, Campendonk, Dix, Feininger, Beckmann, Grosz, Hofer, Kirchner, Schmidt-Rottluff, Meidner, and Nolde.

Originally, the exhibition was intended to be open free of charge on Saturdays, Sundays, and Wednesdays from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. There was apparently a fear that the turnout would not be as high as desired. Perhaps the goal was to ensure the galleries were crowded during those few opening hours. However, any such concerns proved to be unfounded, as from April 11 onward, the exhibition was also open for two hours each afternoon. This resulted in a total opening time of 62 hours for the three-week duration—still a very short period by comparison. Although photographs of the exhibition and visitor statistics are missing, press and eyewitness accounts report an immense turnout. The Berliner Börsen-Zeitung wrote on April 12, 1933: "Never before have exhibitions in Mannheim or Karlsruhe had such attendance as these." Eyewitnesses also reported that the exhibition was "extraordinarily well" attended.

The exhibition had two goals: first, to demonstrate to the public the "aberrations" into which art had developed during the Weimar democracy. Second, it aimed to show visitors how recklessly the governments of the Weimar Republic had squandered tax money on works of so-called "decadent art." While this was the original idea, under Bühler, the exhibition turned primarily into a personal settling of scores with his immediate predecessors in the leadership of the Kunsthalle and with his fellow painters who represented modern art. In doing so, he resorted to methods for which he was criticized not only by the chairman of the Badischer Kunstverein—which had not yet been brought into line (gleichgeschaltet)—but also by those within National Socialist circles.

Critical Reactions

Bühler came up with the idea of presenting "obscene prints" to visitors upon request in an "Erotic Cabinet," which was separated from the rest of the exhibited works. These prints had never been purchased by the Kunsthalle; instead, they were created by students of the Landeskunstschule and were shown without their knowledge. To further stimulate the "base instincts" of the public, the exhibition was closed to anyone under eighteen. Furthermore, the purchase prices displayed beneath the paintings were not converted from inflation-era Marks into the current currency. Consequently, many works were labeled with enormous sums, intended to leave unsuspecting visitors stunned.

Bühler's biggest mistake, however, was including a work by Alexander Kanoldt titled Still Life with Rubber Plant in his exhibition. Kanoldt, one of the leading representatives of the New Objectivity movement, had already joined the NSDAP in May 1932 and was appointed director of the Academy of Fine Arts in Berlin by Minister of Education Bernhard Rust on May 1, 1933—just one day after the Karlsruhe exhibition ended.

This put Kanoldt in a position where he could exert massive pressure on Bühler and hold him accountable for defaming him as a "degenerate artist." Together with the president of the Baden Secession, Edmund von Freyhold—who was also a member of the NSDAP—Kanoldt used Bühler’s exhibition to sharply condemn Baden's cultural policy. Kanoldt and von Freyhold sent written complaints to several influential committees and individuals, such as the Baden Ministry of Education and Culture, the Ministry of Education in Berlin, and the director of the Berlin National Gallery, Ludwig Justi. Kanoldt’s criticism was more than clear. On June 8, 1933, he wrote to the Baden Ministry of Education and Culture, stating among other things:

„If Mr. Bühler believed he could insult me by presenting me as a pseudo-artist in this company, then he is mistaken – I consider this equivalence to be the highest honor ever bestowed upon me! But that was not how it was intended! And since I am one of the few who can defend themselves against the intent to insult, I do so with all decisiveness for the dead! For this exhibition is not only an insult to art, but a devious insult to Baden. [...] One can only watch with regret and, far beyond that, with horror as the Karlsruhe Academy, which once ranked first and of which I consider it a great stroke of luck to have been a student, is to sink down to the level of such intellectual shallowness, when its reconstruction is handed over to such a questionable artistic personality as Bühler embodies. [...] It is incomprehensible how a government could allow such a cultural disgrace."

It should also be noted that Kanoldt passed away in 1939 at the age of 57, and his works were also considered "degenerate" starting in 1937 and removed from all German museums.

A second wave of outrage against Bühler occurred in the spring of 1934. It was triggered by the sale of what was then probably the most significant modern painting in the Karlsruhe Kunsthalle to the Kunsthalle in Basel at a ridiculous price: Street in Åsgårdstrand by Edvard Munch. Following this, numerous art historians and other critics contacted the Baden Ministry of Education and Culture and demanded Bühler’s dismissal. They were joined by representatives of the National Socialist German Students' League (NSDStB), who filed massive complaints with the Baden Ministry of Education and Culture and the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda in Berlin. It thus became clear that a new director for the Badische Kunsthalle had to be found quickly. In July 1934, the position was filled by a new appointee.

Criticism also from the Baden Art Association

In his opening speech for the exhibition, Bühler launched a frontal attack on Max Liebermann, the most prominent representative of German Impressionism and long-standing president of the Prussian Academy of Arts. He referred to him as the "gravedigger of German art." In response, the chairman of the Badischer Kunstverein, Franz Xaver Honold, left the room in protest. Honold, a partner in the law firm of Reinhold Frank—who was later executed as a resistance fighter of the July 20, 1944 plot—was the only person who had the courage to create a public scene during Bühler's tirade against Liebermann. Everyone else remained seated.

Franz Xaver Honold was close to the Centre Party and, despite his demonstration against Hans Adolf Bühler, remained chairman of the Badischer Kunstverein until his early death at the age of 57 in January 1939. Today, Honold is regarded as a representative of that liberal-conservative bourgeoisie in Karlsruhe that maintained a distant to opposing stance toward the National Socialists and became increasingly isolated during the phase of Gleichschaltung (co-ordination). Historical sources indicate that Honold attempted to adapt the association to the political circumstances "out of necessity" in order to ensure its continued existence.