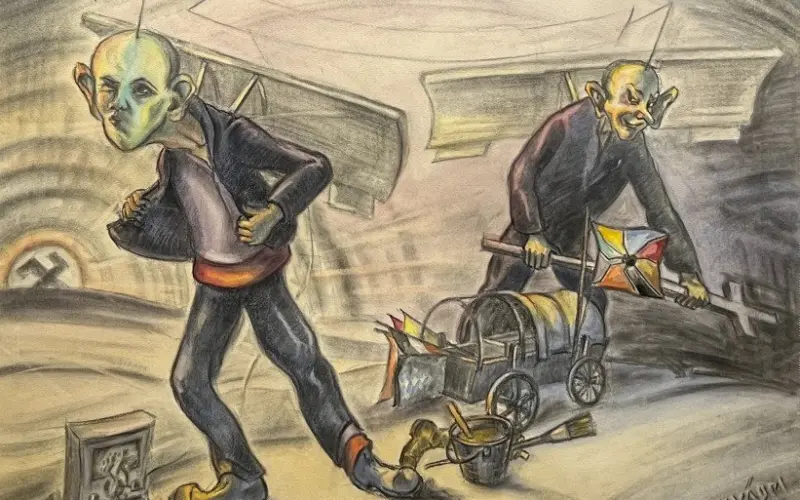

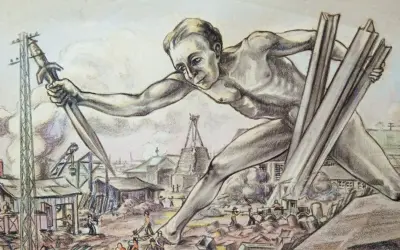

This term refers to the artists who were born around 1900 and lived in Germany and in the territories occupied by the National Socialists. Their works were defamed as entartet—literally degenerate—and their careers were destroyed by the Nazi dictatorship and World War II. After 1945, they were pushed aside by the emerging wave of abstraction and fell into obscurity, until decades later they were rediscovered by art historians.

News

The Lost Generation

The museum project

Our project to establish a museum in Karlsruhe that is dedicated exclusively to the Lost Generation fills a significant gap in the German museum landscape and is a powerful gesture of recognition for those artists who were defamed, persecuted, and ultimately pushed out of cultural memory during the Nazi era. It contributes to the culture of remembrance and makes the mechanisms of exclusion visible.