The term “Lost Generation” refers to a group of artists whose lives and work were profoundly shaped by the political, social, and cultural upheavals of the first half of the twentieth century and who largely disappeared from cultural memory as a result of war, persecution, emigration, or deliberate marginalization. The concept of the “Lost Generation” was significantly shaped by the art historian Rainer Zimmermann, who drew attention to the fate of these painters in 1980 with his book The Art of the Lost Generation.

Especially in the German-speaking world, this generation is closely associated with the experiences of the First World War, the Weimar Republic, and the National Socialist dictatorship. Many of these artists were among the most innovative voices of their time. They worked within movements such as Expressionism, New Objectivity, the Bauhaus milieu, and early Modernism. Their works reflect a profound engagement with the existential experiences of violence, alienation, social change, and political instability. Rather than aesthetic harmony, their artistic practice often centered on rupture, uncertainty, and social critique.

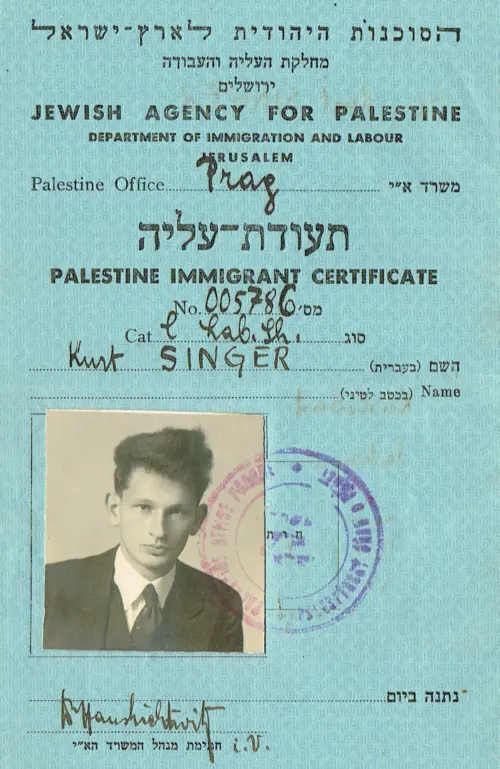

With the National Socialists’ seizure of power in 1933, a systematic persecution of these artists began. Modern art was denounced as “degenerate,” works were removed from museums, and exhibitions were banned. Many artists lost their professional livelihoods, were forced into exile, or were murdered. Others adapted under duress, fell silent, or withdrew into inner emigration. As a result, the artistic development of this generation was abruptly interrupted, and numerous bodies of work remained fragmentary or were lost entirely.

With the invasion of neighboring countries to the East and West by the German Wehrmacht, Jewish artists in these nations, in particular, became victims of Nazi ideology, as they now found almost no means of escape. Just as many Jewish artists in Germany had before them, they now fell into the clutches of the SS and Gestapo and were murdered by the hundreds in concentration camps across Eastern Europe.

After the Second World War, there was no immediate rediscovery of these artists. Cultural reconstruction often focused on new movements or on figures who were already internationally established. Many biographies of the Lost Generation remained unresolved; archives had been destroyed, and works were scattered or anonymized. Only in the later decades of the twentieth century did a gradual art-historical reassessment begin, revealing the extent of this cultural loss.

Today, the “Lost Generation” is increasingly understood as a central connecting link in the history of modern art. Their works not only document aesthetic developments but also serve as historical testimonies to an era in which art and freedom were inseparably linked. The rediscovery of these artists therefore represents more than a mere expansion of the canon: it is an act of cultural remembrance and historical justice.

Engaging with the Lost Generation makes clear how fragile cultural heritage can be when political power instrumentalizes or destroys art. At the same time, it demonstrates that suppressed voices can return—through research, exhibitions, and renewed interest in works that long remained in the shadow of history.